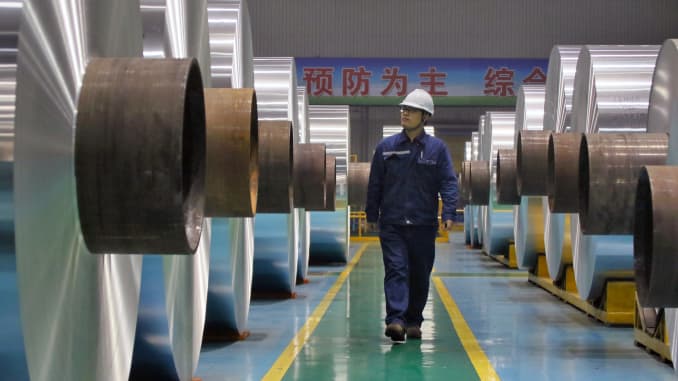

Employees

work on the production line of high-precision sheet aluminium at a

factory of Shandong Weiqiao Pioneering Group Company Limited on November

23, 2019 in Zouping, Shandong Province of China.

Tang Ke | VCG via Getty Images

Widespread disruption brought on by the coronavirus outbreak has hammered global

supply chains and

spurred Chinese companies to declare “force majeure” — a provision that

exempts them from contractual obligations. But experts warn there’s a

high chance such a move may not work.

A force majeure event occurs

when unforeseeable circumstances, such as natural catastrophes, prevent

one party from fulfilling its contractual duties, absolving them from

penalties.

Since late January, the Chinese government has

implemented city-wide lockdowns and large-scale quarantines that

effectively curbed the movements of millions in China as the country

seeks to contain the COVID-19 virus. Those restrictions have hurt

businesses as operations of factories and facilities came to a

near-standstill.

According to the China Council for the Promotion

of International Trade, a government-linked entity, China has

issued 4,811 force majeure certificates as of Mar. 3 due to the

epidemic. They covered contracts worth 373.7 billion Chinese yuan

($53.79 billion),

state media Xinhua reported. Such certificates are issued by the government to companies that apply for them.

In a previous update,

the council said applicants span across 30 industries and sectors with

high applications rate include manufacturing, wholesale and retail and

construction.

Force majeure may not work outside China

But

Chinese entities may face a “rude awakening” when they try to claim

force majeure against counterparties internationally, said Brian

Perrott, a London-based partner at international law firm Holman Fenwick

Willan.

PRC (People’s Republic of China) entities

that have been issued the certificates face a rude awakening if they

think they will allow them to get out of contracts with international

parties.

Brian Perrott

partner at Holman Fenwick Willan

While

such documents may help entities claiming against one another in the

Chinese domestic markets, most claims will not hold up on the global

stage, Perrott told CNBC in an email. “Most of these FM (force majeure)

claims will not succeed,” the law firm added.

“PRC (People’s

Republic of China) entities that have been issued the certificates face a

rude awakening if they think they will allow them to get out of

contracts with international parties,” it added.

That is because

the majority of trading contracts between China and international

parties are governed by English law, which only allows parties to claim

force majeure if the document includes very specific clauses.

Force

majeure clauses in English law contracts are usually “very lengthy and

detailed, and outline exactly which events can be used to trigger FM,”

said Perrott. “They will often specifically refer to epidemics, which

would cover the coronavirus.”

The party claiming force majeure

would then need to prove that their ability to meet the contract was

“impaired” or made “impossible” by the coronavirus. “The latter, in

particular, is extremely challenging to prove. Most FM claims fail,” he

added.

French oil giant Total

has already rejected a force majeure notice from a liquefied natural gas buyer in China, Reuters reported.

‘Catch-all’ vs explicit provisions

Such provisions are only relevant if the contracts have a force majeure clause to begin with.

According

to an analysis by legal technology provider Kira Systems, just 72% of

the contracts reviewed — or 94 out of 130 — included force majeure

provisions. The commercial contracts filed between Feb. 2018 and Feb.

2020 involved at least one Chinese entity.

Of the 94 contracts

with the force majeure provisions, just 13 of them explicitly state that

public health events — such as flu, epidemic, serious illness, plagues,

disease, emergency or outbreaks — would constitute a force majeure

situation, Kira Systems found. Unforeseen public health situations were

not expressly included in the remaining 81 contracts.

“This data

suggests a gap in contract drafting, at least from the perspective of

the entities affected by the coronavirus outbreak seeking to invoke

their force majeure clauses,” wrote Jennifer Tsai, the company’s legal

knowledge engineering associate.

English law

encourages both parties in a force majeure situation to take steps to

mitigate the event and the consequences – even if those actions are

outside the terms of the contract.

Brian Perrott

partner at Holman Fenwick Willan

Most

of the contracts with force majeure provisions reviewed by Kira Systems

also use a general “catch-all” language stating that “any other events

that cannot be predicted and are unpreventable and unavoidable by the

affected Party” constitute force majeure, the company said in its

report. This flexibility means that companies need to consider if the

outbreak constitutes an unpreventable and unpredictable force majeure

event, Tsai wrote.

Of the 94 contracts that included force majeure

provisions, 44% included acts of government in its definition, the Kira

analysis found.

That means that “affected parties could

ostensibly cite the governmental extension of the Lunar New Year

holiday, the mandated closing of businesses, and travel restrictions in

Hubei province and other provinces, as ‘acts of government’ beyond their

control in order to avoid incurring liability for delays in performance

or failure to perform,” said Tsai.

Talk it over

Given

that the coronavirus outbreak is — by most expectations — supposed to

be short-lived, Perrott advises the parties in a contract to resolve the

issues rather than enter a dispute.

A former vice minister at

China’s Ministry of Commerce, Wei Jianguo, told CNBC in an interview on

Sunday, that companies want to maintain their credibility with business

partners. He added that work is picking up in areas outside Hubei, the

epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Wei, who is now vice

chairman and deputy executive officer at Beijing-based think tank, China

Center for International Economic Exchanges, said he expected the

number of new force majeure certificates to fall into the double digits

in the next 10 days.

Perrott advises both parties in a contract to take steps to mitigate any disruptive event due to the viral outbreak.

“English

law encourages both parties in a force majeure situation to take steps

to mitigate the event and the consequences – even if those actions are

outside the terms of the contract,” he told CNBC.

“It’s also good

sense for parties to try to resolve the matter amicably. After all, the

coronavirus is nobody’s fault,” said Perrott.

— Evelyn Cheng contributed to this report.

Comments

Post a Comment